Feb 17, 2026

In conjunction with our Preliminary Documented Safety Analysis (PDSA) approval, we’ve announced our test facility. This is a good moment to highlight what we plan to achieve with our first criticality this summer, what our test is and isn’t, and how it fits into our broader tech maturation roadmap to enable commercialization.

The ultimate development milestone is a full-scale, commercially viable, electricity-producing reactor. We intend to produce electricity with a full-scale reactor, the Mark-1, within 2027, in the same test facility we have established for the Mark-0 pilot reactor. Everything we are doing with the pilot reactor is designed to accelerate our ability to produce electricity through an iterative, incremental development approach.

There are many misconceptions about the value of full-thermal-power versus zero-power testing, which can confuse those outside the industry and lead to opaque assessments of technical progress. We believe it is best for Antares and the industry as a whole to be transparent about the milestones necessary to mature our product. We have built our program around that philosophy: test subsystems early, integrate deliberately, ensure that each experiment is representative of the product we intend to deploy, and then incorporate experimental results to enhance the end-state product.

We have chosen a staged development path built around three validations:

Heat Transfer

Reactors must be able to transport heat from the fuel to a heat exchanger and exchange it with the power conversion system to accurately determine the thermal power at which the reactor can and should operate. This can be done in a nuclear demonstration, but given how short-lived demonstrations often are, irradiation-induced aging of components is negligible. Therefore, the performance of the primary coolant can be validated more quickly and cheaply using an electrically heated surrogate. Furthermore, this is a safe approach to development ahead of a nuclear demonstration.

We completed Milestone 1 through our electrically heated demonstration Unit (EDU) test at NASA Marshall in 2025. This is a milestone we intend to complete again in 2026, with a subsequent iteration of our heat pipe design and control system.Reactor physics

Modern reactor design relies on high-fidelity simulation codes, but simulations must be anchored in real-world measurements. Zero-power critical testing enables us to ground our neutronics and reactor kinetics simulations in reality. This requires us to build a reactor that allows us to collect empirical measurements of reactivity, shutdown margin, kinetics parameters, and flux and power distributions. Collecting this data in a low-power reactor enables us to design and build high-power reactors with greater confidence that our simulations match reality. That is what the Mark-0 demonstration before July 4th is intended to do: validate the nuclear fundamentals of our system. Mark-0 will also be the first demonstration of our instrumentation and control system–the same system that will also be used in Mark-1 and subsequent reactors.

Note that this milestone can only be achieved if the fuel and core layout are sufficiently representative of the commercial product.Full power operation with a Power Conversion System (PCS)

The third stage of development is integrating heat generation and heat transfer into a true prototype power plant. Full-power operation validates the next set of temperature-dependent reactor effects, including reactivity feedback effects, kinetic and dynamic stability, xenon poisoning, and power and flux distributions.

The most important aspect of this milestone is validating the thermal efficiency of the power conversion technology and characterizing the coupled feedback between the reactor and power conversion system. This integrated testing is what Mark-1 is for.

Why the sequence is deliberate

While everything validated by these milestones is necessary, a company could choose to consolidate all milestones into a single test or shift the timing of which performance properties are validated. At Antares, we’ve aimed to achieve ZPC in 2026, since 2023. The reason for this approach is simple. First, using heat pipes as the primary coolant makes it straightforward to validate the performance of our primary coolant and primary heat exchanger through EDUs. Second, many reactor physics and control systems properties can be validated at low to zero power. Lastly, starting with zero power ensures low radiation-induced activation in the test facility and allows us to reuse the fuel, enabling us to proceed rapidly with our electricity-producing test. If we tested at full power without a power conversion system, as other companies intend, it could be as long as a year before we could safely work inside the test facility to enable a subsequent test, which risks delaying full completion of milestone three.

These three milestones are not meant to be exhaustive. Even after an electricity-producing prototype is built, the work is just beginning. The next step is to iterate from First-of-a-Kind (FOAK) to true Nth-of-a-Kind (NOAK) performance with commercially viable economics. This will require component redesign, investments in materials irradiations to qualify for longer life, fuel performance advances, manufacturing scale-up, and supply chain consolidations.

Where to from here?

We, as Americans, are closer than ever to a nuclear renaissance. The next four years will likely see more new reactors than the preceding forty. At the same time, we must maintain humility and acknowledge how far we still have to go for success to endure and scale. At Antares, our approach to testing involves subsystem testing followed by integrated effects testing that validates the milestones listed above. A heat pipe reactor design allows rapid iteration on EDUs, since iteration on heat pipes is faster than on turbopumps used in HTGRs. Under the Department of Energy’s Pilot Program, we will achieve zero to low power criticality with a full-scale reactor (Mark-0) and control system, satisfying milestone two. At this stage, we will still be on the “20-yard line”.

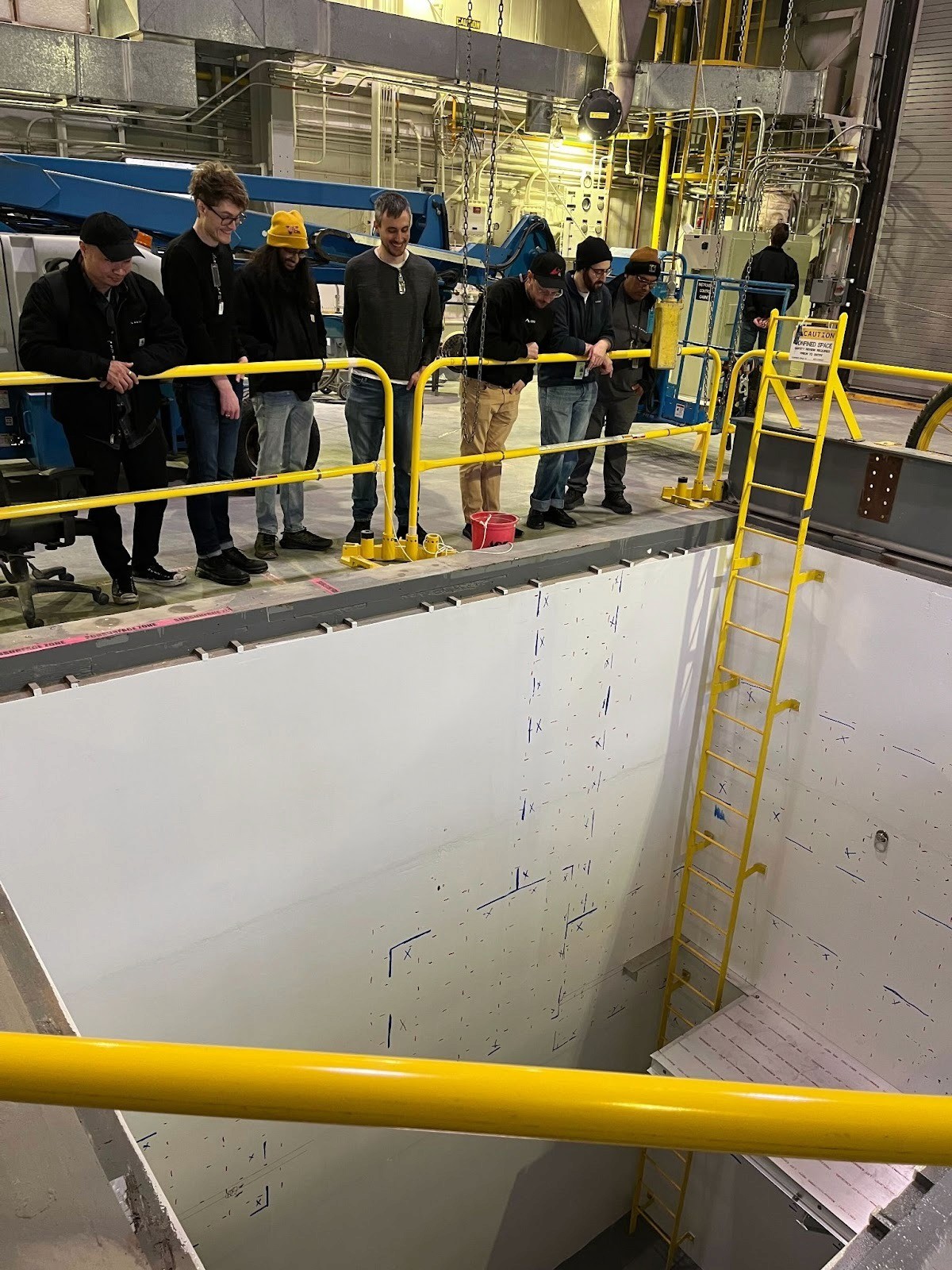

True performance validation for any reactor design comes from graduation to a full-scale electricity-producing system. Currently, none of the DOE-authorized reactor tests slated for 2026 will be electricity-producing systems. It is important for all reactor developers to consider how they will transition from reactor tests in 2026 to electricity-producing systems as soon as possible. At Antares, we have a clear plan. In 2027, we will use the same test facility at INL and the same batch of HALEU TRISO fuel compacts to scale up to full power and produce electricity using our nitrogen-closed Brayton cycle. We have a very real chance to be the first new electricity-producing American advanced reactor of the 21st century!

2026 has already seen unprecedented acceleration in the development of privately built reactor prototypes. We at Antares are moving at a pace once considered preposterous. In just 2 years, we’ve tested an EDU, established a reactor test site, begun fabricating HALEU TRISO fuel for two reactors in partnership with BWXT, and received the first-ever approved PDSA for a reactor. As we accelerate, we must also ensure the industry does not lose sight of its long-term objectives – safe, reliable, economical power. Unrealistic short-term expectations will lead to disappointment, and customers, government partners, congressional offices, and investors may turn bearish on the nuclear renaissance. My hope is that, by accurately framing a simple set of preliminary technology maturation milestones, we can align interests for enduring, scalable success. Onward to criticality!